S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe)

S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe) Augmentation of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Antidepressant Nonresponders With Major Depressive Disorder: A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial

Published Online:1 Aug 2010https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081198

Abstract

Objective

Despite the progressive increase in the number of antidepressants, many patients with major depressive disorder continue to be symptomatic. Clearly, there is an urgent need to develop better tolerated and more effective treatments for this disorder. The use of S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), a naturally occurring molecule that serves as a methyl donor in human cellular metabolism, as adjunctive treatment for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder represents one such effort toward novel pharmacotherapy development.

Method

Participants were 73 serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) nonresponders with major depressive disorder enrolled in a 6-week, double-blind, randomized trial of adjunctive oral SAMe (target dose: 800 mg/twice daily). Patients continued to receive their SRI treatment at a stable dose throughout the 6-week trial. The primary outcome measure for the study was the response rates according to the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM–D).

Results

The HAM–D response and remission rates were higher for patients treated with adjunctive SAMe (36.1% and 25.8%, respectively) than adjunctive placebo (17.6% versus 11.7%, respectively). The number needed to treat for response and remission was approximately one in six and one in seven, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of SAMe- versus placebo-treated patients who discontinued the trial for any reason (20.6% versus 29.5%, respectively), due to adverse events (5.1% versus 8.8%, respectively), or due to inefficacy (5.1% versus 11.7%, respectively).

Conclusions

These preliminary results suggest that SAMe can be an effective, well-tolerated, and safe adjunctive treatment strategy for SRI nonresponders with major depressive disorder and warrant replication.

Major depressive disorder is a prevalent and potentially debilitating medical illness that can often be quite challenging to treat. For example, it has been reported that as many as one-half of all patients enrolled in two academic-based depression specialty clinics did not achieve remission despite receiving a series of adequate trials of antidepressant therapies (1). Moreover, in the first level of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression study, only about 30% of patients had achieved remission following up to 12 weeks of therapy with citalopram (2), with many patients remaining symptomatic despite second-, third-, or fourth-line treatment approaches (3). Results of studies like these serve to remind clinicians and researchers alike of the urgent need to continue to develop new as well as novel treatments for major depressive disorder.

S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), a naturally occurring molecule available commercially in Europe since the late 1970s as a treatment for depression and other conditions, was released in the United States in a stable, enteric-coated oral formulation as an over-the-counter dietary supplement under the Dietary Health and Supplement Act of 1999 (4). SAMe, folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine are linked in the one-carbon cycle, since homocysteine and 5-methylene tetrahydrofolate, a product of folate, are required for the formation of SAMe (4). SAMe is found throughout the human body, with particularly high concentrations in the liver, adrenal glands, and pineal gland (5). SAMe also appears to be uniformly distributed in the brain, where it serves as the major donor of methyl groups required in the synthesis of neuronal messengers and membranes (4).

The antidepressant efficacy of SAMe has been studied in numerous randomized, controlled trials involving depressed adults in Europe and the United States (6, 7). Specifically, six randomized, double-blind studies have compared parenteral SAMe monotherapy with a tricyclic antidepressant for the treatment of major depressive disorder; six randomized, double-blind studies have compared parenteral SAMe monotherapy with placebo; and one randomized, double-blind study has compared parenteral SAMe monotherapy with placebo as well as a tricyclic antidepressant (7). In parallel, three randomized, double-blind studies have focused on the use of oral SAMe monotherapy versus tricyclic antidepressants for the treatment of major depressive disorder; three studies have focused on the use of oral SAMe monotherapy versus placebo; and one study has focused on the use of oral SAMe monotherapy combined with the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine versus placebo (adjunctive therapy, but not in resistant populations) (7). Although many of these studies were most likely underpowered (only five had >25 patients randomly assigned per treatment arm), meta-analyses of these trials consistently support a potential therapeutic role of parenteral and oral SAMe in the treatment of depression. For example, in a meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized clinical trials comparing SAMe with placebo or with tricyclic antidepressants (8), oral and parenteral SAMe showed superior response rates relative to placebo and equivalent response rates relative to tricyclic antidepressant monotherapy. A subsequent meta-analysis of depression trials commissioned by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (6) similarly concluded that SAMe (parenteral or enteral) was associated with an overall effect size of 0.65 when compared with placebo, translating to a clinically meaningful improvement on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM–D) of approximately five to six points (9). On the other hand, when SAMe was compared with active comparators (tricyclic antidepressants), the effect size was only 0.08 (95% confidence interval: –0.17–0.32), suggesting an equivalent efficacy. Unfortunately, however, despite ample evidence indicating a potential antidepressant role for SAMe, there is a relative paucity of data focusing on the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral SAMe as monotherapy or as adjunctive treatment for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder.

Despite the progressive development of dozens of antidepressant agents, evidence suggests that more than one-half of all patients treated with antidepressant monotherapy will fail to experience remission of their major depressive episode. As a result, developing safe, well-tolerated, and effective treatments that would help bring about remission among these patients who are antidepressant partial responders or nonresponders is of paramount importance. In light of studies suggesting its potential efficacy, safety, and tolerability when employed as monotherapy for major depressive disorder, SAMe represents a unique opportunity for novel treatment development as adjunctive therapy for patients who are antidepressant nonresponders. In a preliminary study conducted by our group, Alpert et al. (10) reported response and remission rates of 50% and 43%, respectively, among 30 outpatients with serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI)-resistant major depressive disorder treated with open-label adjunctive oral SAMe (400–800 mg/twice daily). Unfortunately, however, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials focusing on the use of oral SAMe as augmentation of antidepressants are lacking. The purpose of the present study was to examine the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of SAMe as augmentation of SRIs for patients with major depressive disorder who were antidepressant nonresponders. In order to achieve this objective, we conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of SAMe augmentation of SRIs.

Method

Study Overview and Eligibility Criteria

The study was a single-center, 6-week, randomized, double-blind trial of SAMe augmentation of SRIs for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder. Institutional review board-approved written informed consent was obtained from all study patients before any study procedures were conducted. Eligibility was assessed primarily during the screen visit and secondarily during the baseline visit, which occurred 7 days after the screen visit.

Patient inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18–80 years; criteria met during the screen and baseline visits for current major depressive disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM–IV [11]), as assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P [12]); HAM–D score of at least 16 at both screen and baseline visits; treatment with an SRI at adequate doses (a minimally adequate dose was defined as 20 mg/day or more of fluoxetine, citalopram, or paroxetine; 10 mg/day or more of escitalopram; 50 mg/day or more of sertraline; 60 mg/day or more of duloxetine; and 150 mg/day or more of venlafaxine; this was defined historically); treatment with SRIs for an adequate duration (defined as treatment at an adequate dose for at least 6 weeks; this was also defined historically). At the baseline visit, patients must have been taking a stable dose of an SRI for the past 4 weeks.

Patient exclusion criteria were as follows: breastfeeding women, pregnant women, or women of childbearing potential who were not using a medically accepted means of contraception; patients who demonstrated a greater than 15% decrease in depressive symptoms as reflected by the HAM–D total score between the screen and baseline visits; serious suicide or homicide risk, or unstable medical illness as assessed by an evaluating clinician; active alcohol or drug use disorder within the last 6 months; history of mania, hypomania (including antidepressant-induced), psychotic symptoms, or seizure disorder; clinical evidence of untreated hypothyroidism; failure to experience sufficient symptom improvement following more than four antidepressant trials during the current major depressive episode; or prior course of SAMe or intolerance to SAMe at any dose.

Study Procedures

Patients who were found to be eligible during the baseline visit were enrolled in the study and randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups in a 1:1 fashion. One group of patients received two dummy pills daily, each identical to a 400 mg SAMe pill in appearance (administered as one pill twice daily). The second group received two 400 mg SAMe pills daily (administered as one pill twice daily).

Postbaseline study visits occurred weekly for a total of six postbaseline visits. All patients had their number of pills doubled upon completion of 2 weeks of treatment (2 pills twice daily). SRI doses remained constant during the 6-week study. Subjects who were unable to tolerate the study medications, per protocol, were withdrawn. All patients were instructed to return any excess medication at each visit. A pill count was conducted to corroborate the study drug record. Protocol violation was defined as <80% compliance by pill count.

The HAM–D and Clinical Global Impression (CGI [13]) severity and improvement scales were administered during all postscreen visits.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome measure for the present study was defined as the difference in response rates, according to HAM–D ratings, between the two treatment groups. The study data set was defined using the intent-to-treat approach, consisting of all patients randomly assigned to treatment. Severity of depression at endpoint for patients who prematurely discontinued the trial was defined using the last-observation-carried-forward approach. Response according to HAM–D ratings was defined as a ≥50% reduction in scores during treatment (or a final score of ≤7).

Secondary outcome measures included continuous change in HAM–D scores and CGI severity ratings during treatment. Secondary outcome measures also included the proportion of patients meeting remission status according to HAM–D scores (final score of ≤7) or CGI severity ratings (score of 1 at endpoint) and response status according to CGI improvement ratings (score of <3 at endpoint). Fisher’s exact test was employed for the comparison of dichotomous outcomes, while analysis of variance, controlling for baseline scores, was employed for the comparison of continuous outcomes. All tests were conducted as two-tailed, and alpha was set at 0.05 for all tests.

Results

A total of 73 patients (44 women [60.2%]) were randomly assigned to treatment (34 were assigned to adjunctive placebo and 39 to adjunctive SAMe). Baseline clinical and demographic data for these patients are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Antidepressant Nonresponders Randomly Assigned to Treatment With S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe) or Placeboa

Of the 73 patients who were randomly assigned, 55 (75.3%) completed the 6-week trial: 24 (70.5%) of those receiving adjunctive placebo and 31 (79.4%) of those receiving adjunctive SAMe. Four patients discontinued placebo and two discontinued SAMe because of inefficacy; three placebo and two SAMe patients discontinued because of intolerance; two placebo and three SAMe patients discontinued for other reasons; and one patient from each treatment group was lost to follow-up evaluation. Of the patients who remained in the study for at least 2 weeks (week 2 was the dose-escalation week), all but two patients who were treated with SAMe had a dose escalation to 1,600 mg (two patients did not undergo the dose escalation because of intolerance), while all but one patient treated with placebo underwent a dose escalation to two placebo pills twice daily (one patient did not undergo the dose escalation because of intolerance).

Adverse events for patients who received adjunctive placebo versus SAMe were similar (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in laboratory results and vital signs at endpoint between the two treatment groups (Table 3), with the exception of a slightly higher mean supine systolic blood pressure reading for patients treated with adjunctive SAMe relative to placebo (mean difference: 3.1 mm Hg [SD=0.3]). A similar finding was not observed for other blood pressure measures. There was also a nearly significant difference (p=0.05) for higher weight at endpoint among patients treated with SAMe relative to patients treated with placebo (both groups demonstrated a numerical reduction in weight during the course of the trial, with placebo-treated patients losing, on average, 1.5 lbs more than SAMe-treated patients). There were no serious adverse events reported during the study. In addition, there were no reports of serotonin syndrome when combining SAMe and serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which has been previously reported in the literature (14).

Table 2. Adverse Events Among Antidepressant Nonresponders Randomly Assigned to Treatment With S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe) or Placeboa

Table 3. Vital Signs, Weight, and Lipid Profile of Antidepressant Nonresponders Randomly Assigned to Treatment With S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe) or Placeboa

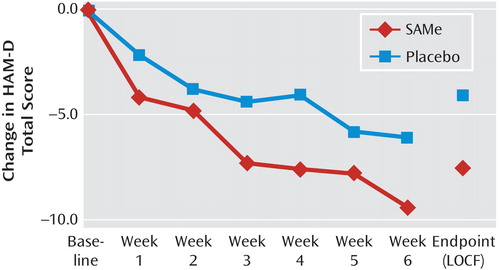

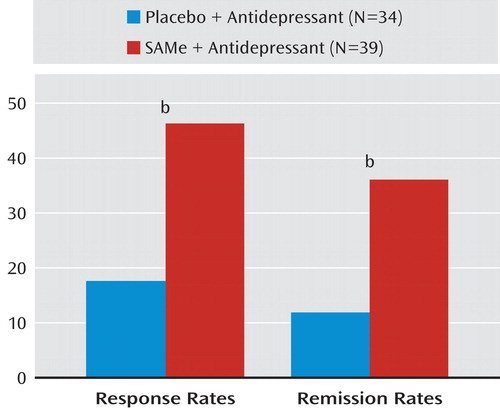

Changes in HAM–D scores from baseline in the two treatment groups are shown in Figure 1. There was a nearly significant difference (p=0.1) for lower endpoint HAM–D scores among SAMe-treated patients (mean: 11.1 [SD=6.1]) relative to placebo-treated patients (mean: 15.8 [SD=6.2]). Overall, according to HAM–D ratings, six patients treated with placebo responded and four remitted, while 18 patients treated with SAMe responded and 14 remitted, with both outcome measures statistically significant in favor of adjunctive SAMe versus placebo (p=0.01 and p=0.02, respectively [Figure 2]). CGI severity ratings at endpoint were numerically but not statistically higher for the placebo group (mean: 3.4 [SD=1.1]) relative to the SAMe group (mean: 2.7 [SD=1.3]). Remission rates (placebo group: N=2/34 versus SAMe group: N=10/39, p=0.03) as well as response rates (placebo group: N=7/34 versus SAMe group: N=20/39, p=0.02), according to CGI ratings, were greater for SAMe-treated patients than for placebo-treated patients.

Discussion

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral SAMe tosylate as adjunctive therapy for patients with major depressive disorder who are antidepressant nonresponders. The results of this study provide preliminary evidence suggesting that SAMe can be an effective, relatively well-tolerated, and safe adjunctive treatment strategy for SRI nonresponders with major depressive disorder, and our findings warrant replication. Specifically, significantly more patients treated with adjunctive SAMe experienced clinical response (the a priori primary outcome of the study) and remission during the course of the study. Response rates for SAMe-treated patients versus placebo-treated patients were 36.1% versus 17.6%, respectively, while remission rates were 25.8% versus 11.7%, respectively. The number needed to treat for response and remission was approximately one in six and one in seven, respectively, both within the range of what is considered clinically relevant (15). In addition, adjunctive SAMe was found to be relatively well tolerated compared with adjunctive placebo, with similar discontinuation rates as a result of intolerance between the two treatment groups (SAMe: 5.1% versus placebo: 8.8%, yielding a number needed to harm of approximately one in 27). Finally, no serious adverse events were reported in this trial, although a nearly significant difference toward lesser decreases in weight (p=0.05) as well as statistically significant greater increases in supine systolic blood pressure (p=0.04) was noted among SAMe-treated patients relative to placebo-treated patients, which, if confirmed in future studies, may be of clinical relevance.

Several potential mechanisms of action have been proposed to mediate the antidepressant effects of SAMe. It functions primarily as a methyl donor in a variety of biochemical reactions, including the methylation of catecholamines (16). Since depression is thought to be related to dysfunction in neural circuits involving dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, SAMe could act as an antidepressant by shifting the synthetic equilibrium in the direction of greater monoamine synthesis. In addition to methylation reactions, SAMe has been proposed to increase serotonin turnover, inhibit norepinephrine reuptake, and augment dopaminergic activity (16). Other investigations have suggested the presence of antidepressant mechanisms based on SAMe’s effects on brain neurotrophic activity, inflammatory cytokines, cell membrane fluidity, and bioenergetics (16, 4). Should the antidepressant effects of oral SAMe be confirmed in more definitive trials, future studies examining its potential underlying mechanism of action would then be warranted.

There are several limitations to this study, which should be taken into account when interpreting the main findings. First, the study aimed to provide preliminary evidence on the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of adjunct oral SAMe in major depressive disorder and, as a result, was probably underpowered to consistently detect moderate effect sizes. Thus, our findings, both those that do and do not reach conventional statistical significance thresholds, suggest that this adjunctive intervention shows significant promise to justify larger scale, adequately powered tests of efficacy as well as tolerability and safety (for instance, with respect to supine systolic blood pressure and weight change). A second limitation was that it involved treatment with SAMe or placebo for a total of 6 weeks. Whether adjunctive SAMe is more effective than placebo when administered for longer treatment durations remains undetermined. A third limitation was the absence of a differential dose treatment arm, which could have yielded important information regarding whether higher or lower target doses of SAMe are more effective than the target dose we employed (1,600 mg daily). A fourth limitation was that the study did not employ an active treatment comparator arm, which could have yielded interesting information regarding the relative efficacy, tolerability, and safety of adjunctive SAMe versus other treatment strategies for antidepressant nonresponders. Finally, it is not possible to directly generalize the present findings to patient populations who were excluded from this trial (i.e., children, adolescents, patients with active alcohol or drug use disorders, patients with unstable medical disorders, patients at imminent risk of suicide, and patients taking non-SRI antidepressants).

In conclusion, the results of the present study, which is the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of SAMe augmentation to be conducted in this patient population, provide preliminary evidence suggesting that SAMe can be an effective, relatively well-tolerated, and safe adjunctive treatment strategy for SRI nonresponders with major depressive disorder. Further studies are required to confirm whether oral SAMe should be added to the antidepressant treatment armamentarium.

Received Aug. 21, 2009; revision received Nov. 18, 2009; accepted Dec. 28, 2009. From the Center for Treatment-Resistant Depression, Depression Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Papakostas, Center for Treatment-Resistant Depression, Depression Clinical and Research Program, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 15 Parkman St., WACC #812, Boston, MA 02114; gpapakostas@partners.

Dr. Papakostas has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Evotec AG, Inflabloc Pharmaceuticals, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre Laboratories, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth; has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Evotec AG, GlaxoSmithKline, Inflabloc Pharmaceuticals, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre Laboratories, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth; he has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Pharmaceuticals, the National Institute of Mental Health, Pamlab, Pfizer, and Ridge Diagnostics (formerly known as Precision Human Biolaboratories); and he has served on the speaker’s bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support for other clinical trials in the form of donated medications from Amarin (Laxdale), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cederroth, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Nordic Naturals, and Swiss Medica; he has received consulting and writing honoraria from Pamlab; he has received speaking honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Nordic Naturals, Pfizer, Pamlab, and Virbac as well as from Reed Medical Education (a company working as a logistics collaborator for the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy); and he has received royalty income from Back Bay Scientific for PMS Escape (patent application pending). Dr. Alpert has received research support from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Cephalon, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, J and J Pharmaceuticals, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Organon, Pamlab, Pfizer, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi/Synthelabo, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he has participated on the advisory boards of or as a consultant to Eli Lilly, Pamlab, and Pharmavite; and he has received speaker’s honoraria from Eli Lilly, Janssen, Organon, and Reed Medical Education. Dr. Fava has received research support from Abbott Laboratories, Alkermes, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Bio Research, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Clinical Trial Solutions, Eli Lilly, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GlaxoSmithKline, J and J Pharmaceuticals, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, NARSAD, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the National Institute on Drug and Alcohol Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, Novartis, Organon Inc., Pamlab, Pfizer, Pharmavite, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he has served on the advisory boards of or as a consultant to Abbott Laboratories, Amarin, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Biovail Pharmaceuticals, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, CNS Response, Compellis, Cypress Pharmaceuticals, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal GmbH Janssen Pharmaceutica, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, J and J Pharmaceuticals, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Methylation Sciences, Neuronetics, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Organon, Pamlab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite, Precision Human Biolaboratory, PsychoGenics, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Schering-Plough, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Takeda, Tetragenex, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he has received speaker and publishing fees from Advanced Meeting Partners, the American Psychiatric Association, AstraZeneca, Belvoir, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Imedex, Novartis, Organon, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy/Reed-Elsevier, UBC Pharma, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; he is a shareholder with Compellis; he has patent applications for sequential parallel comparison of design and for a combination of azapirones and bupropion in major depressive disorder; and he receives copyright royalties for the following Massachusetts General Hospital assessment tools: the Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire, the Sexual Functioning Inventory, the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire, the Discontinuation-Emergent Sign and Symptom scale, and SAFER. Ms. Shyu reports no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Funded by a National Institute of Mental Health grant (5-K23 MH-069629).

SAMe and matching placebo pills were provided (free of cost) by Pharmavite.

The education programs conducted by the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy were supported through Independent Medical Education grants from pharmaceutical companies co-supporting programs along with participant tuition. Commercial entities currently supporting the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy are listed on the Academy’s website (www.mghcme.org).

ClinicalTrials.gov registry number, NCT00093847.

References

1Petersen T , Papakostas GI , Posternak MA , Kant A , Guyker WM , Iosifescu DV , Yeung AS , Nierenberg AA , Fava M : Empirical testing of two models for staging antidepressant treatment resistance. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005; 25:336–341 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2Trivedi MH , Rush AJ , Wisniewski SR , Nierenberg AA , Warden D , Ritz L , Norquist G , Howland RH , Lebowitz B , McGrath PJ , Shores-Wilson K , Biggs MM , Balasubramani GK , Fava M ; STAR*D Study Team: Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:28–40 Link, Google Scholar

3Rush AJ , Trivedi MH , Wisniewski SR , Nierenberg AA , Stewart JW , Warden D , Niederehe G , Thase ME , Lavori PW , Lebowitz BD , McGrath PJ , Rosenbaum JF , Sackeim HA , Kupfer DJ , Luther J , Fava M : Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:1905–1917 Link, Google Scholar

4Papakostas GI , Alpert JE , Fava M : SAMe in the treatment of depression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2003; 5:460–466 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5Bottiglieri T : S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe): from the bench to the bedside: molecular basis of a pleiotropic molecule. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75(suppl):1151S–1157S Crossref, Google Scholar

6Hardy M , Coulter I , Morton SC , Favreau J , Swamy V , Chiappelli F , Rossi F , Orshansky G , Jungvig LK , Roth EA , Suttorp MJ , Shekelle P : S-Adenosyl-l-Methionine for Treatment of Depression, Osteoarthritis, and Liver Disease (Publication number, 02-E04). Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2002 Google Scholar

7Papakostas GI : The role of S-adenosyl methionine in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70(suppl 5):18–22 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8Bressa GM : S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) as antidepressant: meta-analysis of clinical studies. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 1994; 154:7–14 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9Hamilton M : A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56–62 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10Alpert JE , Papakostas G , Mischoulon D , Worthington JJ , Petersen T , Mahal Y , Burns A , Bottiglieri T , Nierenberg AA , Fava M : S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) as an adjunct for resistant major depressive disorder: an open trial following partial or nonresponse to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or venlafaxine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004; 24:661–664 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM–IV). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994 Google Scholar

12First MB , Spitzer RL , Gibbon M , Williams JBW : Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID–I/P, Version 2.0). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1995 Google Scholar

13Guy W(ed): Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Program Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised (Publication number, 76-338). Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976 Google Scholar

14Iruela LM , Minguez L , Merino J , Monedero G : Toxic interaction of S-adenosylmethionine and clomipramine. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:522 Link, Google Scholar

15Papakostas GI , Thase ME , Fava M , Nelson JC , Shelton RC : Are antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 62:1217–1227 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16Alpert JE , Papakostas GI , Mischoulon D : One-carbon metabolism and the treatment of depression: roles of S-adenosyl-l-methionine and folate, in Natural Medications for Psychiatric Disorders: Considering the Alternatives, 2nd ed. Edited by Mischoulon DRosenbaum J. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008, pp 68–83 Google Scholar